Data augmentation methods are a staple when training computer vision models, with methods like flipping, resizing, cropping and blurring used so ubiquitously that they are a foregone conclusion in most systems.1 These methods help improve model robustness such that anyway you change the image of a cat, the model still recognizes the item in the picture as a cat. This is relatively straight forward since all aforementioned techniques keep the main object the same such that a cat remains a cat, and does not somehow magically morph into a dog. But does this work for NLP as well?

Naive Data Augmentation

Text is composed of discrete tokens rather than continous vectors, so what does blurring or flipping even mean in this setting? It turns out that cropping and rotation can be approximated by first converting a sentence into a dependency parse and then pruning branches or shifting them around.2 If we define blurring as finding nearby pixels for mixing, then we can view swapping tokens within a sentence as an analogous operation. Swapping is part of Easy Data Augmentation (EDA) which also includes randomly inserting or deleting tokens, as well as synonym replacement.3 Auto-augment for images automatically learns an optimal mixture of augmentations4, which has inspired similar forms of automatically designing augmentation policies for dialogue.5 These all roughly fall under the umbrella of surface form alteration which changes the actual tokens of text to create new examples.

Another popular family of augmentation techniques is latent perturbation where the raw text is first mapped into some hidden state before being transformed back to natural langauge. Variational Auto-encoders (VAEs) fit nicely into this paradigm since you can perturb the latent state before decoding to theoretically generate an arbitrary number of augmentations.6 Posterier collapse aside, such a generative model can be hard to train since it requires learning the entire distribution of outcomes. Oftentimes, it is much easier to learn a direct mapping from one piece of raw text to another, where the hidden state is untouched. This is basically paraphrasing.7 If we jump to a pivot langauge in the middle of encoding and decoding, this is Round Trip Translation (RTT).8 There are countless other techniques in the realm (see 9 for one survey), but a last one worth mentioning is Mix-match which interpolates the hidden states of two examples and also the hidden states of their labels to produce new examples.10 Temperature sharpening may also be applied.

While all these methods have seen some success in NLP, naively applying them to intent classification and other dialogue tasks may not be so straightforward because they can easily alter the semantic meaning of an utterance. To see why, take for example the sentence “I would prefer not to eat Indian food, it’s too spicy”. Suppose we were to perform word replacement, and switch Indian to American: “I would prefer not to eat American food, it’s too spicy”. Then the utterance doesn’t make a lot of sense, and the user’s intent has also been altered. Suppose token dropout were used instead: “I would prefer to eat Indian food”. Now the user’s preference has been completely inverted! Unlike in the image setting, tiny perturbations can cause large semantic shifts in text.

Label Preserving Data Augmentation

To preserve semantics as we generate new examples, the augmentation technique ought to have an awareness of the importance of certain entities or phrases before performing its transformation. For example, rather than dropping random tokens, this can be accomplished more intelligently by only focusing on stopwords or other low order segments as determined by a POS tagger. When operating in a latent space, consistency training induces robustness applying general perturbations around a region of a label, while encouraging the model to still maintain the same prediction.11 A typical loss function to enforce matching predictions can be a cross entropy loss. Others have also tried MSE, KL-divergence, JSD or any other distance metric.12

Taking this a step further, rather than operating at the token-level, we can expand this to encompass entire segments where different phrase fragments are shuffled or recombined to form new utterances as part of compositional augmentation.13 Typically, the focus is on the unimportant spans in order to avoid accidentally changing the label, but if we have access to an ontology, we can actually target the label by switching known values for slot-filling with other values belonging to that same slot.2

If the goal is to make sure the label is preserved, we can actually work on the problem in reverse as well! Concretely, we can consider creating new examples from scratch starting from the labels themselves using text generation methods. Language model (LM) decoding pre-trains a language model to auto-regressively predict a text span composed of a label followed by a corresponding utterance. During inference, the model is fed the label alone and asked to produce a novel example.14 Alternatively, we can use the label set to write out templates which are then paraphrased by humans into natural language.15 This can be applied to the dialogue setting by having entire conversations written out in template format before paraphrasing into natural text.16

Even though the methods now preserve labels, they still face a host of other issues. To start, there is no single method that is reliably useful.17 This lack of consistency holds not only when dealing with a wide range of NLP tasks, but even when optimizing just for specific tasks such as intent classification.12 Moreover, most methods have only been studied on classification, rather than on complicated tasks such as dialogue state tracking. Consequently, there is no consensus to how well these augmentation methods work in practice. But what if the goal isn’t even model robustness on in-domain examples? What if what we really want is to build scalable dialogue systems that can survive the complexity of real-life conversations?

Data Augmentation for Diversity

Using data augmentation to achieve robustness on out-of-domain (OOD) examples requires a shift in mindset from targeting label quality towards focusing on label diversity. This mirrors a similar shift in computer vision in optimizing for both Affinity and Diversity.18 Template paraphrasing may generate high quality annotations since we know the labels unfront, but the breadth of coverage is limited by the number of manually crafted templates. LM decoding fine-tuned on your dataset may start to overfit to the distribution it has encountered. In order to produce novel examples then, we must inject some alternate prior into the data distribution.

Auxilliary supervision techniques obtain data following a different distribution by literally using a separate dataset. Essentially, some small seed set can be used to query a large pool of unlabeled utterances to find examples that are close enough to maintain the label, but far away enough to expand the coverage.19 In order to maintain the label preserving properties, an additional filtering process can be applied. An alternative to moving towards a different distribution is to add noise to the data manifold, which has also been shown to improve out-of-domain robustness.20

Text generation based on large-scale pretrained LMs may be especially well-suited for promote diversity since it was (likely) trained on data unrelated to the downstream task, yet can still output coherent examples. To extract the information stored in its billions of parameters, we can lean on tricks such as beam search, nucleus sampling, or top-k sampling when applied to LM decoding.9 Text in-filling with a masked language model (MLM) can also be utilized in a similar manner.17 And although it hasn’t happened yet, using prompt-based methods to generate new examples is likely right around the corner. These method resolve OOD issues to some extent, but are unsatisfying because they fail to cover all possible conversational scenarios. But since the space of possible topics is infinite, does that mean data augmentation is fundamentally flawed?

To see how this may work, we first have to recognize that the limitation in coverage is not a flaw of data augmentation, but rather a general difficulty of building dialogue systems. So to make things practical, we will not aim to build systems that can discuss any topic. Instead, we limit the conversations to pertinent aspects helpful for solving specific use cases (ie. buy a chair, find an email, book a flight). Additionally, we set expectations by letting users know that the chatbot has its limitations. However, this leads to a new issue since the current techniques expand coverage of the solution space in an arbitrary manner, and while we no longer need to expand to an infinitely large horizon, we still have to expand to new domains in a targeted and controllable manner.

Augmentation as Conditional Generation

Controllable data augmentation allows for scaling to new domains and use cases in a reliable manner, which is absolutely essential for building products on top of this technology. To achieve this, we must first clearly define what we mean by use cases. Specifically, use cases can be considered individual skills (ie. find a restaurant, make a reservation, update a reservation to add more peoeple, cancel a reservation) that all belong to some domain (ie. restaurant reservation management). Suppose we are able to build a dialogue system that can handle three use cases, but we would now like to expand into a fourth. More than just haphazard data augmentation, we would like to synthesize new training examples in a scalable fashion targeted to help the model learn this fourth skill.

By conditioning on the new use case we care about when performing generation, we should be able to create new examples for model training that specifically fit our criteria. Concretely, suppose the fourth skill we want to add is the ability for the dialogue system to converse about restaurant cancellations. Then, we outline the actions agents must take to handle cancellations.21 The discrete actions can be translated into templates using automated means, which are then paraphrased into natural language. In contrast to direct paraphrasing, the goal here would be to produce examples in totally new directions rather than re-hashing the existing data.

Once we have some starting examples, we can then use data augmentation in a traditional manner to produce many more. In conclusion, in order to make data augmenation useful for scalable product development, we moved away from using it as a means of promoting robustness, and instead as an alternate form of data collection. The only step left is making this entire process operate efficiently, which is admittedly easier said than done.

Data Augmentation Taxonomy

To recap, we have explored a whirlwind of data augmentation options, starting with ideas inspired from computer vision and gradually moved closer to techniques specialized for scaling development of dialogue systems. What we discovered along the way is that key application of data augmentation is not necessarily for improving model performance, but rather for dealing with long-tail out-of-domain use cases. To wrap up, we now organize the smorgasboard of augmentation techniques into a more formal structure for future study.

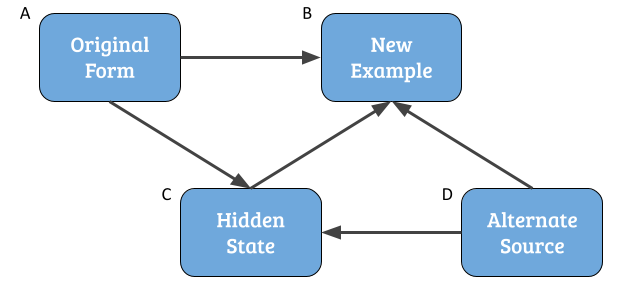

One way to organize all the different types of augmentation methods is to think of the end goal in mind —- namely the newly formed training example. A key benefit is this allows us to formulate the solution space with a directed acyclic graph (DAG) which ensures that our taxonomy is collectively exhaustive. In doing so we end up with the diagram above which outlines five key categories of data augmentation.

- Surface Form Alteration (A –> B): EDA, Character Swapping, Synonym Replacement, Rules-based Systems

- Latent Perturbation (A –> C –> B): Pivot languages, VAEs, GANs, Direct paraphrasing

- Text Generation (C –> B): LM Decoding, Text In-filling, User Simulation

- Auxiliary Supervision (D –> B): External data pool, kNN retrieval on unlabeled utterances, Weak supervision

- Template Paraphrasing (D –> C –> B): M2M, Overnight, Agenda-based Simulators

An interesting observation is that while template paraphrasing seems like a subgroup, according to the DAG it is a parent level method. Ultimately it seems that while all methods are useful, some are more useful than others.

-

Chen et al. (2020), A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations ↩

-

Louvan and Magnini, 2020), Lightweight Data Augmentation for Low Resource Slot Filling and Intent Classification ↩ ↩2

-

Wei and Zou (2019), Easy Data Augmentation Techniques for Boosting Performance on Text Classification Tasks ↩

-

Cubuk et al. (2020), AutoAugment: Learning Augmentation Policies from Data ↩

-

Niu and Bansal (2019), Automatically Learning Data Augmentation Policies for Dialogue Tasks ↩

-

Zhao et al. (2017), Learning Discourse-level Diversity for Neural Dialog Models using Conditional VAEs ↩

-

Prakash et al. (2016), Neural Paraphrase Generation with Stacked Residual LSTM Networks ↩

-

Sennrich et al. (2016), Improving Neural Machine Translation Models with Monolingual Data ↩

-

Feng et al. (2021), A Survey of Data Augmentation Approaches for NLP ↩ ↩2

-

Berthelot et al. (2020), MixMatch: A Holistic Approach to Semi-Supervised Learning ↩

-

Xie et al. (2020), Unsupervised data augmentation for consistency training ↩

-

Chen et al. (2021), An Empirical Survey of Data Augmentation for Limited Data Learning in NLP ↩ ↩2

-

Jacob Andreas (2020), Good-Enough Compositional Data Augmentation ↩

-

Anaby-Tavor et al. (2020), Do not have enough data? Deep learning to the rescue! ↩

-

Wang et al. (2015), Building a Semantic Parser Overnight ↩

-

Shah et al. (2018), Bootstrapping a Neural Conversational Agent with Dialogue Self-Play ↩

-

Chen and Yin (2021), Data Augmentation for Intent Classification ↩ ↩2

-

Lopes et al. (2021), Tradeoffs in Data Augmentation: An Empirical Study ↩

-

Chen and Yu (2021), GOLD: Improving Out-of-Scope Detection in Dialogues using Data Augmentation ↩

-

Ng et al. (2020), SSMBA: Self-Supervised Manifold Based Data Augmentation for Improving OOD Robustness ↩

-

Chen et al. (2021), ABCD: Action-Based Conversations Dataset ↩